Aging isn’t always a smooth, gradual process. New research suggests that humans actually experience two distinct periods where the aging process noticeably accelerates – around age 44 and again at around 60. These findings challenge the common perception of aging as a steady decline and highlight the complex biological shifts happening within our bodies throughout life.

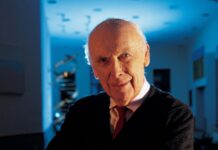

This conclusion comes from a 2024 study published in Nature Aging that tracked molecular changes associated with aging in a group of 108 adults over several years. Led by geneticist Michael Snyder of Stanford University, the research team analyzed a vast dataset – over 246 billion data points – encompassing various biomolecules like RNA, proteins, lipids, and gut microbiome samples.

The study found that roughly 81 percent of the molecules examined showed distinct shifts in abundance during one or both of these accelerated aging periods. These changes weren’t gradual; they presented as clear “peaks” at those specific ages.

Mid-Life Milestone: The Forty-Fourth Turning Point

Around age 44, the research team observed significant changes in molecules related to lipid metabolism, caffeine and alcohol processing, and cardiovascular health. This peak also coincided with alterations in skin and muscle function. Notably, men exhibited these same molecular shifts even though women were undergoing menopause or perimenopause during this period, suggesting other underlying factors contribute to these mid-life changes.

A Second Wave: Entering the Sixth Decade

The second peak occurred around age 60 and involved molecules related to carbohydrate metabolism, caffeine processing, cardiovascular health, skin and muscle function, immune regulation, and kidney function. This suggests a broader systemic impact of aging during this stage.

What Does This Mean?

Understanding these abrupt shifts in the aging process is crucial for developing better strategies to mitigate age-related diseases. While previous research had hinted at non-linear aging patterns in animals like fruit flies, mice, and zebrafish, this study provides concrete evidence of similar “stepped” aging in humans.

The relatively small sample size and limited range of ages studied in this particular project highlight the need for further investigation. Future studies with larger and more diverse cohorts will help refine our understanding of these acceleration points and potentially uncover specific triggers or contributing factors behind them.

This deeper understanding could pave the way for personalized interventions aimed at slowing down or even reversing age-related decline during these critical periods.