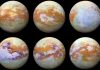

Scientists have confirmed the presence of a highly infectious and often fatal virus – cetacean morbillivirus – in humpback whales in the Arctic for the first time. The discovery, made using drones to collect samples from whale blowholes in northern Norway, raises concerns about the spread of disease in previously unaffected marine ecosystems.

First Detection in Arctic Waters

The virus, which has caused mass die-offs of porpoises, dolphins, and whales in other regions like the North Atlantic and Mediterranean, was detected in whale blow samples analyzed by researchers from Nord University. Published in BMC Veterinary Research in mid-December, the study confirms that this deadly pathogen is now circulating in Arctic waters.

“It has never been reported in that area before,” explains Helena Costa, a veterinarian who led the research. “We kind of expected that some of the species that migrate would bring it in.”

How the Study Was Done

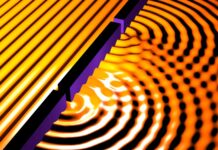

Traditionally, scientists collect tissue samples via skin biopsies, a more invasive method. The new study used drones to gather whale blow – exhaled breath – offering a less disruptive way to sample marine mammals. This is crucial because some whales may show no external symptoms even when infected.

Why This Matters

The virus attacks the respiratory and neurological systems of marine mammals, leading to severe illness and death. The fact that it has now been found in the Arctic suggests that migratory whales are spreading the virus into previously isolated populations. The researchers also suggest that gaps in previous monitoring may have hidden the virus’ presence for longer than previously thought.

The implications are significant. Increased surveillance is needed to track the spread of cetacean morbillivirus and understand how it affects Arctic whale populations. The study also highlights the value of non-invasive research methods, like drone sampling, for studying vulnerable wildlife without causing harm.

The discovery serves as a stark reminder that even remote ecosystems are not immune to disease transmission. Further research is critical to predict the virus’ long-term impact on Arctic marine life.