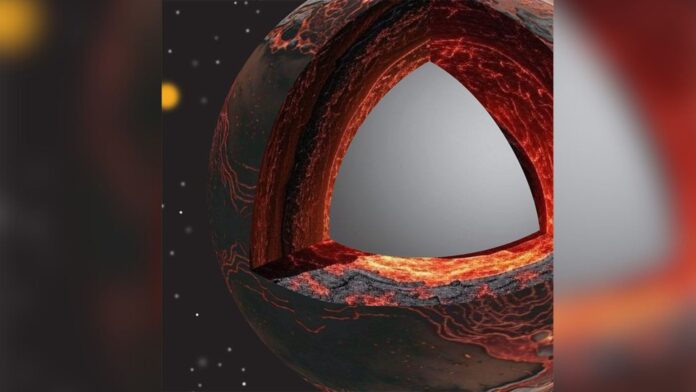

Deep within Earth, two massive, mysterious structures in the mantle may hold vital clues about how our planet formed and why it became habitable. These continent-sized “lava puddles,” located nearly 1,800 miles beneath the surface, defy current planetary formation models.

The Enigmatic Structures

Scientists first identified these unusual regions – known as large low-shear-velocity provinces and ultra-low-velocity zones – by analyzing how seismic waves travel through Earth. The waves slow dramatically as they pass through these areas, suggesting a unique chemical composition that differs from surrounding mantle rock.

Geodynamicist Yoshinori Miyazaki, who led the research, emphasized the significance: “These are not random oddities; they are fingerprints of Earth’s earliest history.” Understanding their origin could unlock key insights into the planet’s evolution.

The Basal Magma Ocean Hypothesis

Early Earth was once a molten magma ocean. As it cooled, the mantle should have stratified into distinct layers. However, the existence of these massive, amorphous structures suggests something else occurred.

The new research proposes that silicon and magnesium may have leaked from Earth’s core into the mantle during its early stages. This chemical mixing would have resulted in uneven cooling, forming the anomalous structures as remnants of an ancient “basal magma ocean.”

Implications for Planetary Habitability

These core-mantle interactions likely influenced Earth’s cooling, volcanic activity, and atmospheric development. If the structures originated from this process, it could explain why our planet developed the conditions necessary to support life.

As study co-author Jie Deng explained, “The idea that the deep mantle could still carry the chemical memory of early core-mantle interactions opens up new ways to understand Earth’s unique evolution.”

The findings, published in Nature Geoscience, highlight how combining planetary science, geodynamics, and mineral physics is essential for unraveling the planet’s deepest mysteries. Understanding these structures provides a window into Earth’s earliest history and why it became the habitable world we know today.