Recent research suggests that in developed nations, human lifespan is now approximately 50% determined by inherited genetic factors and 50% by environmental influences. This finding, based on reanalysis of decades-old twin studies from Denmark and Sweden, represents a shift from earlier estimates that placed genetic influence at just 25%.

The Changing Role of Genetics

The updated estimate doesn’t mean environment is less important — rather, it acknowledges a stronger genetic component than previously understood. As Joris Deelen of Leiden University Medical Center explains, “At least 50% is attributable to environmental factors, so environment still plays a major role.” This is crucial because heritability isn’t fixed; it varies depending on the population and the conditions they live in.

The principle is simple: if conditions are uniform (like a perfectly flat field for wheat), genetics will dominate variations in outcome (height). But in varied environments, external factors become more decisive. The same applies to humans.

How the Study Works

Researchers analyzed data from twins born between 1870 and 1935 in Sweden and Denmark. By focusing on deaths from age-related conditions (like heart attacks) rather than accidents or infections, they found that genetics accounted for roughly half of lifespan variation. This aligns with observations in animal aging studies, where genetic factors often play a more dominant role.

Why This Matters

Identifying the specific gene variants that influence lifespan could be a key step toward developing drugs that extend human life. However, so far, few longevity-associated genes have been discovered. This gap suggests that the genetics of aging are incredibly complex, with potential trade-offs between different traits. For instance, genes that suppress autoimmune diseases might also weaken resistance to infections.

The Future of Longevity Research

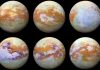

One challenge is that most ongoing studies (like the UK Biobank) involve participants who are still alive, limiting statistical power. Additionally, comparing lifespan across species reveals even more dramatic genetic constraints. A mouse genome will never allow for a lifespan exceeding a few years, while a bowhead whale’s genes enable survival for over two centuries.

The study reinforces the idea that human longevity is a product of both nature and nurture. Further research will need to unravel the complex interplay between genes and environment to unlock the full potential of life extension.