The human stomach handles incredibly corrosive substances – strong enough to dissolve metal – yet somehow remains intact. This isn’t accidental; the stomach has evolved specialized defenses to withstand its own digestive power. The question of why stomach acid doesn’t burn through the organ is a crucial one, as it reveals how biological systems manage extreme chemical processes.

The Harsh Reality Inside Your Stomach

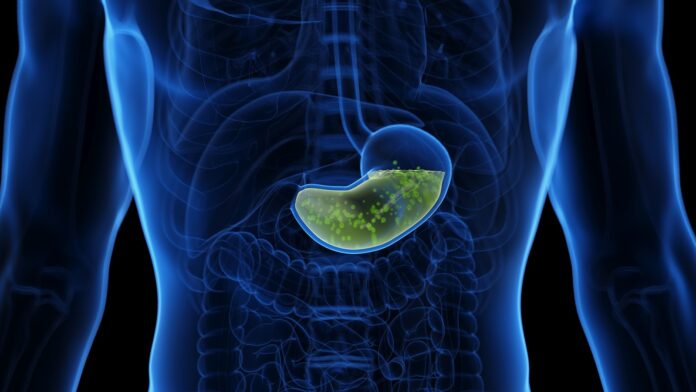

The stomach’s primary function is to break down food into absorbable components. This requires powerful chemicals, primarily hydrochloric acid, alongside digestive enzymes like pepsin and lipase. These substances aren’t just strong enough to break down food; they could damage the stomach itself if not for natural protection.

Dr. Sally Bell of Monash University explains that the stomach’s role is to reduce food to its basic parts before they reach the small intestine, which is why it needs such a potent environment. But this also means constant exposure to materials that would otherwise be dangerous.

The Mucus Barrier: Nature’s Shield

The stomach lining is protected by a thick layer of mucus. This isn’t just any mucus; it’s alkaline and rich in bicarbonate, effectively neutralizing the acid before it can harm the stomach walls.

As Dr. Bell explains, these cells produce a “very thick, sticky layer…that buffers the acid.” This barrier is constantly renewed by epithelial cells, ensuring continuous protection. Without it, acid and enzymes would quickly erode the stomach lining, leading to ulcers and, eventually, perforation.

Defense Beyond Digestion

The acidic environment serves a second purpose: killing harmful bacteria. Dr. Benjamin Levy III of the University of Chicago Medicine notes that gastric juices destroy pathogens and prevent bacterial overgrowth, especially from foodborne illnesses. This is a critical survival mechanism that ensures the body doesn’t succumb to infection from contaminated food.

What Can Go Wrong?

Despite the stomach’s resilience, the protective layer can be compromised. Overuse of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen damages the stomach lining by inhibiting the production of prostaglandins, reducing mucus and bicarbonate secretion. Lifestyle factors like smoking and excessive alcohol consumption also weaken the protective barrier.

Even diet plays a role: acidic or spicy foods can overwhelm the stomach’s defenses, triggering irritation or acid reflux.

Bacterial Threats and Treatment

Certain bacteria, like Helicobacter pylori, can circumvent the stomach’s defenses by degrading the mucus layer. These infections can be treated with antibiotics, but they demonstrate that even a well-protected organ isn’t entirely invulnerable.

The stomach’s ability to withstand its own corrosive environment is a testament to the power of natural selection. This organ has evolved to perform a critical function—digestion and defense—while simultaneously protecting itself from its own destructive power.