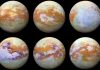

The iconic twin sunset of Tatooine from Star Wars isn’t just science fiction. Planets orbiting two stars, called circumbinary planets, do exist in the Milky Way. However, astronomers have found far fewer than expected, and a new study suggests Einstein’s theory of general relativity may be to blame.

The Missing Planets: A Statistical Anomaly

Given that roughly 10% of single-star systems host planets, scientists predicted a similar rate for the 3,000 known binary star systems in our galaxy. That would mean around 300 circumbinary planets. Yet, only 14 have been confirmed among the 6,000+ exoplanets discovered so far. This discrepancy puzzled researchers, prompting them to explore the underlying physics.

The Role of General Relativity and Orbital Chaos

The new research, led by Mohammad Farhat at UC Berkeley, points to the chaotic interplay of gravity in binary systems. The two stars orbit each other elliptically, and any planet caught in their gravitational dance experiences a slow, spiraling shift in its orbit – a process called precession.

Crucially, the stars themselves also precess due to the effects of general relativity. As the stars move closer over time, their precession speeds up, while the planet’s slows down. When these rates align, the planet’s orbit becomes dangerously stretched.

Destabilization and Ejection

This resonance creates extreme orbital instability. According to the study, either the planet spirals inward and is torn apart by the stars, or it’s flung out of the system entirely. This effect is particularly pronounced in tight binary systems, where the stars orbit very closely (periods of a week or less).

Why We Might Be Missing Them

The study also highlights a potential observational bias. Current planet-hunting missions like Kepler and TESS are most effective at finding planets in tight binary systems, the very ones where instability is highest. This means that the lack of detections might not be due to an actual scarcity, but rather to the fact that these planets are short-lived or difficult to observe.

Ultimately, the Milky Way might harbor hundreds or thousands of Tatooine-like worlds. The challenge now is refining our search methods to detect them before gravity tears them apart or flings them into interstellar space.